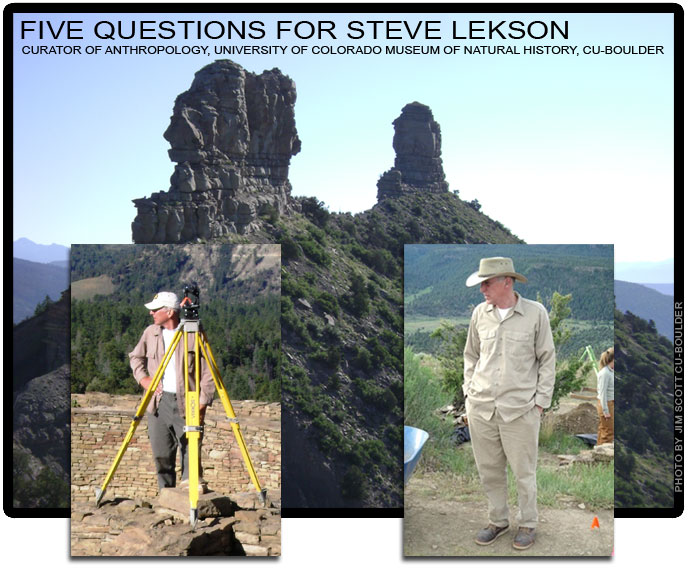

Steve Lekson has stirred up a lot of dust in his time. He's spent years researching prominent archaeological sites, including Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, Yellow Jacket at Mesa Verde in Colorado, and Casas Grandes, known as Paquimé, in Mexico.

But he also likes to shake up conventional wisdom. For instance, he contends the peoples of Chaco, known for using celestial objects to align settlements, used similar orientations to migrate and settle in other areas both north and south along the 108th meridian. (See his book "The Chaco Meridian: Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest," AltaMira Press, 1999).

Such thinking has earned him praise and raised some eyebrows. Some have called him one of the greatest minds of this generation; others have called him just plain wrong. He takes it all in stride with good humor. In the opening of "Chaco," he writes, "This book is not for the faint of heart, or for neophytes. If you are a practicing Southwestern archaeologist with hypertension problems, stop. Read something safe."

His research focuses on the politics, human geography and the architecture of peoples who inhabited Colorado and the Southwest so long ago. He came to the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1997 to head the museum and field studies graduate program. Fieldwork and the laboratory analyses of artifacts and samples are passions, but he also enjoys working with the CU Museum of Natural History, where he is curator of anthropology. While he oversees and uses the museum's anthropology collection in his research and teaching, he also has been bringing the museum into compliance with federal law regarding some artifacts. The law requires institutions that receive federal funding to return cultural items — such as sacred objects and human remains — to their respective Native American peoples.

— Cynthia Pasquale

1. What are you currently researching?

My field research currently includes three sites: Pinnacle Ruin in central New Mexico, Chimney Rock in southwestern Colorado and the Black Mountain site in southern New Mexico. Each of these sites is key to a particular question in Southwestern archaeology.

Pinnacle Ruin appears to represent a village of migrants from Mesa Verde and thus tells us about the "abandonment" of the Four Corners in the 13th century. Chimney Rock is a spectacular site, an outlier of the great 12th-century center at Chaco Canyon. Black Mountain appears as the largest village between the 11th-century Mimbres collapse and the 13th-century rise of Casas Grandes; it may represent the historical transition between those two famous societies.

The research has been undertaken by CU graduate and undergraduate students. In all three projects, we are collaborating with other institutions: universities, nonprofits, local CRM (cultural resource management) firms, etc.

Pinnacle Ruin and Chimney Rock have been my favorite projects so far. Both are important for archaeological issues, and both were spectacular sites in amazing settings, with productive collaborations.

(For more information on Lekson's research, listen to a recent lecture he gave at the University of New Mexico.)

2. You were president and CEO of Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, which allows the public to join archaeological digs in southwestern Colorado. How important do you think it is to allow the public to be able to participate in such endeavors?

It's critical to communicate archaeology's science and stories to larger audiences, and it's largely acknowledged by my field that archaeology does not do a great job of doing that. Crow Canyon is one approach: letting a limited number of interested laypeople participate alongside professional archaeologists. Other media reach larger audiences: for me, most recently, books. And I get dragged into quite a few videos, too.

3. Most sites are researched, then reburied. What are your feelings about this method?

Almost all sites are backfilled. That is, after limited excavations are completed, the earth removed is put back into the excavations to preserve the rest of the site. Leaving an excavated ruin open requires a commitment and budget for long-term care and repair. The National Park Service has the ability to do this, but CU does not.

4. How do science, previous research and new ideas play into your final research report?

All of archaeology, beyond the measurement of a room or photograph of a feature, requires interpretations based on various kinds of information. I'd say most of my research is interpretation based on the archaeological facts and a wide range of outside context for those facts. Archaeology is empirically based and acts in many ways like science, but it's also history and proceeds in many ways like the humanities.

What I seem to be able to do is see connections, relationships and implications among my and others' interpretations that others might miss. Much of my recent work has been based on other archaeologists' research, re-combining old data and projects in novel ways — for example, "The Chaco Meridian."

5. Your new book, "A History of the Ancient Southwest," has received excellent reviews. In the introduction, you say the book and your views might annoy some archaeologists and Indians. Have you indeed annoyed some folks?

So far the reaction has been positive, but of course you hear the nice stuff first. "History of the Ancient Southwest" has, so far, gotten good reviews and some very nice personal messages: Timothy Pauketat, a leading Midwestern archaeologist, described it as "one of the most provocative and forward-looking books in archaeology today." And Phillip Tulwaletstiwa, a respected Hopi Pueblo Indian, wrote: "A significant work of creative genius ... This is THE BOOK by which to measure archaeological progress for years to come."

However, I'm pretty sure that several of my interpretations are not going to go down well, because I relate historical events and trends across research domains that conventionally are seldom compared or understood as part of a larger question. Archaeologists are often fairly territorial, so I imagine that not everyone will welcome my conclusions.

Want to suggest a faculty or staff member for Five Questions? Please e-mail Jay.Dedrick@cu.edu

|